The Indian Legal History- from the times of Origin of State to the English East India Company - PART-3 (Modern India)

The British could leave and half India wouldn't notice us leaving just as they didn't notice us arriving. All our reforms of administration might be reforms on the moon for all it has to do with them. - J. G Farrell

With the coming of the English East India Company came a new era of legal system in India which established a new legal base in the Indian subcontinent. The influence of the Englishmen were seen in every hook and corner of the Indian society and that it led to a massive change in the society that flourished in those times. The last part of this series is going to be a long reading but this would be very effective in understanding of various circumstances which led to such a huge transition in the legal field of India. But... how did it all started?

The Charter of 1600

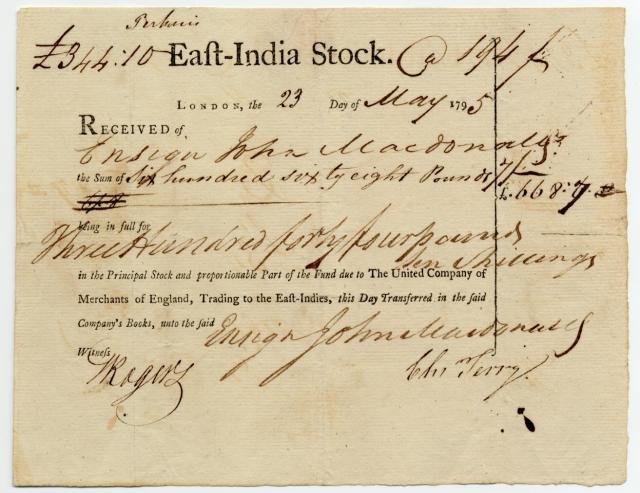

The First East India Company was incorporated in England under a Charter granted by Queen Elizabeth on 31stDecember, 1600. Its official title was ‘the Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies’. It was given the exclusive right of trading in all parts of Asia, Africa and America. No other British subject could trade in this area without obtaining a licence from the Company. The charter was granted for 14 years and it could be renewed for another 15 years only if it did not affect the Crown and its people. The company was managed by Court of Directors.

Powers of the Company: The Company was granted certain limited powers of legislation. The charter authorised the Company to make bye-laws, ordinances etc, for good government, for its servants and officers and for advancement of trade and traffic. The company could also impose fine, penalties and punishment for disobedience of its laws but they were not to be contrary to the laws and customs of England.

The Charter of 1609

The British King James I, renewed the Charter of the Company on May 1st, 1609. As the trade of the East India Company was flourishing well and was also profitable to England, its monopoly of trade was made perpetual there being no limit as to the tenure of the Company. However, the company’s tenure could be terminated with 3 years notice in case it was detrimental to the British interests.

British Settlement at Surat and Administration of Justice (1613-1687)

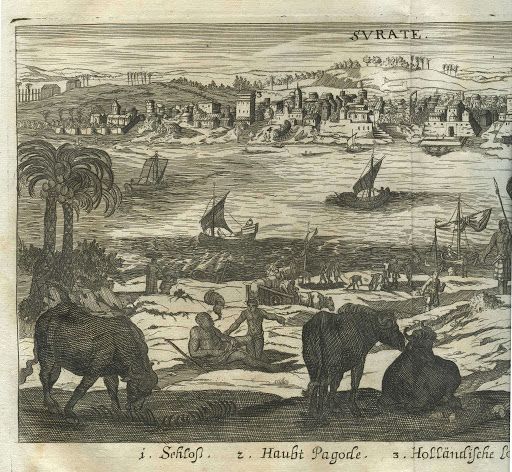

After landing on the Indian soil, the foremost task before the Company was to find out a suitable place as a centre for its trade. The Company selected Surat for this purpose as it was an important commercial centre and enjoyed the status of an International port under the reign of Mughal emperor Jahangir. Portuguese were already there in occupation of this place and there was a clash in 1612 and the Portuguese were finally ousted from Surat.The King of England, James I, sent Sir Thomas Roe to India in 1615 to secure certain concessions from the Mughal Emperor and he was successful in getting some concessions. Thus, the Englishmen were allowed to carry their trade freely and establish a factory at Surat with some concessions like-

- They were allowed to live in accordance with their own laws and religion without any local interference.

- The disputes amongst the Englishmen inter-se were to be settled by their own tribunals.

- The disputes between the Englishmen and the natives were to be settled by the local native authorities.

- All cases of complaints and controversies relating to Englishmen were to be looked into by the Kazi of the place who was to safeguard their interests and ensure justice for them. The Kazi was also directed to treat Englishmen with respect and courtesy.

The Administration of Justice at Surat was the first foot step of the British towards bringing about dynamic change in the Indian Legal System. As a result of these privileges secured by them, the Company established a factory at Surat in 1618 with a ‘Governor’ or a ‘President’ as its head. The working of the native tribunals suffered from many serious defects. Bribery and corruption was rampant and the judicial officers were arbitrary in their decisions. Consequently, the Englishmen did not like to be tried by the native courts and exploited the situation to their advantage by taking law into their own hands. The Company was then allowed to take decisions in their own hands. They were allowed to settle disputes in the hands of their Company's President and asked the Mughal Governors and Qazis for speedy justice.

British Settlement at Madras and Administration of Justice (1639-1726)

The East India Company had a factory at Masulipattam which was merely an agency working under the Chief factory of Surat. In 1639, one of the members of the Masulipattam factory, Francis Day secured permission from the local Hindu chief to construct a fortified English factory on a strip land. This fort was named as Fort.St.George and the Englishmen and other Europeans lived inside it. The company, in this fortified settlement, was empowered to mint money and govern Madraspatnam which was a small village near Company’s fort. This fortified settlement came to be known as the ‘White Town’ because of its all white residents. A village inhabited by local natives grew up adjacent to this English settlement and came to be known as ‘Black town’. In course of time the entire territory comprising White town and Black town developed into the city of Madras. It was only in 1665 that madras factory which was subordinate to Surat was raised into the status of Presidency.

The administration of justice in Madras before 1726 can conveniently be studied under the following 3 distinct phases:

First Phase (1639 to 1665) - In the Black town, prior to British settlement, choultry courts were functioning for administering justice to the natives residing in Madraspatnam.

- Charter of 1661

It was at a later stage that the Charter of 1661 granted by the British King Charles II to the English Company introduced radical changes in the existing judicial system. This charter authorised the Company to appoint Governors and other officers in India. The Governors in council of each place so appointed by the company were empowered to hear and decide all civil as well as criminal cases of the servants of the Company and those living under its jurisdiction according to the laws of England and could execute judgement accordingly. As a result of this charter, the natives residing within the territorial jurisdiction of company’s settlement also came under the authority of the Government and Council whether they were employees of the company or not. Thus the Charter of 1661 introduced two significant changes in the judicial administration, namely:

- Judicial powers were centralised in the Governor and Council who was also the head of the Company’s executive Government.

- The administration of justice was to be carried out according to the laws of England. Obviously, this was most advantageous for the Englishmen but detrimental to the interests of Indian natives whose local traditions, customs and usages were completely disregarded.

Second Phase (1678-1686) - The second phase of the evolution judicial system in Madras commences from 1678 when Streynsham Master became the Governor of Madras. According the Judicial Plan of 1678, the Choultry court was reorganised. The native law officers, namely, the Adigars were replaced by the English Servants of the company. They were known a pay-master, the mint-master and custom-master and all the three were to sit as Judges in the choultry court twice a week. An appeal from this court lay to the High Court of Judicature which consisted of the Governor of madras and his Council. Thus a hierarchy of courts was created for the first time.

Third Phase (1686-1726) - The main feature of this phase of judicial administration was the establishment of Admiralty Court in Madras in 1686. The company enjoyed monopoly of trade yet many private English merchants and traders were still carrying on unauthorised trading which resulted into great loss to the East India Company. Apart from this, there was a considerable rise in crimes on high seas which also had to be settled by an efficient court. The British Crown granted a Charter to the Company in 1683 which extended the powers of the Company to establish more than one Court at places wherever deemed necessary. Each court was to consist of one legal expert who would be well versed in civil law and two Indian merchants to help the Judge in explaining the usage and laws of the natives.

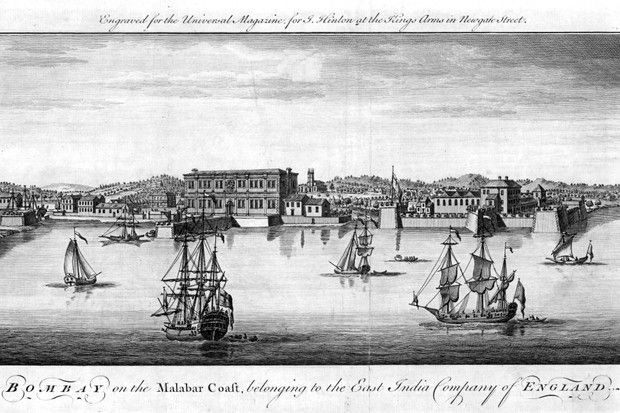

British Settlement at Bombay and Administration of Justice (1668-1728)

In course of time, Surat lost its importance as a trading centre and the Company considered Bombay more suitable for its trading activities. Therefore, the headquarter of the President and Council was shifted to Bombay in May 1687 and since then Bombay became one of the precious trading centre for the Company.

The administration of Justice in Bombay can also be divided under three phases-

First Phase (1668-1683) - The Charter of 1668 empowered the Company to frame law and ordinances for the administration of the territory of Bombay and exercise judicial control over it. The company was empowered to impose punishments by way of fine, imprisonment and could even pass death sentence. Later on, the Company was also authorised to mint money at Bombay. A government proclamation was issued on August 1, 1672 whereby Portuguese law was completely abolished from Bombay and English law was introduced in it place.

Second Phase (1684 – 1690) - The functioning of the court was similar to that of the admiralty Court at Madras and it decided civil and criminal cases besides the usual admiralty and maritime disputes.

Third Phase (1718-1726) - After a gap of about 30 years, the British judicial system in Bombay revived again with the establishment of a Court of Judicature under Lawrence Parker on March 25, 1718.

British Settlement at Calcutta & Administration of Justice (1690-1727)

Some Englishmen landed at Sutanati on the bank of river Hoogly in 1690 and constructed a fortified factory named Fort William. The foundation of Fort William (present Kolkota) was laid by an Englishman Job Charnock on August 24, 1690. The East India Company appointed an English member of the Governor’s Council as ‘Collector’ in 1700 who was empowered to collect revenue and decide civil, criminal and revenue cases of the native inhabitants.

The administration of Justice in Calcutta was very dynamic in its character. The Charter of 1726 is considered to be one of the pioneer step in the judicial administration

The Charter of 1726

The main reasons which necessitated the Charter of 1726 may be briefly summarised as follows:

- The judicial administration and the working of courts in the three Presidency towns of India were unsatisfactory.

- With the growth in company’s trade and commercial activities in India, the population of British Settlements had increased considerably and, therefore, more cases were coming to the courts for adjudication.

- The Company desired that the power of courts should be derived from a competent authority so that their decisions would have a binding force and uniformity in judicial administration could be achieved.

- Encouraged by the successful working of the Corporation at Madras, the Company wanted to establish similar Corporations at Bombay and Calcutta.

- Many Englishmen who settled in India died leaving behind considerable movable and immovable property. This created problems before Company relating to distribution and disposal of their assets.

Finally, the Judicial Charter was granted by the British King George I on September 24, 1726. The main provisions of the Royal Charter of 1726 were as follows :

- Mayor’s Court in Presidency Towns: The Mayor and nine Aldermen of each Corporation formed a Court of Record which was called the ‘Mayor’s Court’. It was empowered to decide all the civil cases within the Presidency town and the factories subordinate thereto. The Mayor together with two other English Aldermen formed the quorum. The court was to hold its sitting not more than three times a week. Being a Court of Record, the Mayor’s Court could commit persons for its contempt. The process of the Court was to be executed by the Sheriffs, the junior members of the Court who were initially nominated but subsequently chosen annually by the Governor and Council.

- Crime and punishment: The Mayor’s Court had no criminal jurisdiction. It was only a Court of civil and testamentary jurisdiction. The Governor and five senior members of the Council were appointed as Justice of Peace in each Presidency for the administration of criminal justice. They could arrest persons accused of crimes and punish them for petty offences. The Charter of 1726 introduced the trial of criminal offences with the help of ‘Grand’ and ‘Petty’ juries. Thus technical forms and procedures of criminal judicature of England were introduced through this Charter in India.

- Jury Trial in Criminal Cases: Jury has always remained an important institution in the criminal law administration of England. The Charter of 1726 provided that criminal cases in Presidencies be decided with the help of Grand Jury and petty Jury. The Grand jury which consisted of 23 persons was entrusted with the task of presenting persons suspected of having committed a crime. It is for this reason that it was also called as ‘Jury of Presentment’. After the indictment had been found, the prisoner was tried by Petty Jury who heard both sides on issues of facts and if they returned a verdict of ‘guilty’, the accused was sentenced by the Court of Quarter Sessions. It is significant to note that along with the Charter of 1726, the Company sent to each Presidency, a list of statutes, law-books and instructions etc., which contained details of procedure to be followed in civil and criminal trials and testamentary cases. This was intended to maintain uniformity in the functioning of the law courts in all the Presidencies and follow the English law. Another reason for adherence to the English law was that the proceedings of the Mayor’s Court had to be submitted annually to the Company’s Council in England.

Working of Mayor’s Court of 1726

The period from 1726 to 1753 witnessed frequent disputes and clashes between the Government and the Mayor’s Court. The Mayor’s Courts being the Crown’s Court exerted their judicial independence which made the Councils unhappy. The Councils had been divested of their power in matter of appointment and tenure of Aldermen under the Charter of 1726. They also did not have any voice in the appointment of the Mayor since he was to be elected by the Corporation independently. The cumulative effect of the judicial scheme envisaged by the Royal Charter of 1726 was that the Corporation and Mayor’s Courts were completely independent of the executive Government. Thus the Charter of 1726 adopted the principle of independence of judiciary to a considerable extent which was a fortunate development in the legal history of India.

The Adalat System

Grant of Diwani and judicial Plans of Warren Hastings - With the victory in the Battle of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), the Company became territorial sovereign and supreme authority in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. It was in 1765 that Mughal Emperor Shah Alam-II who still claimed sovereignty, transferred the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the British Company in lieu of Rs.26 Lakhs per annum. ‘Diwani’ was a term used for fiscal administration and meant the collection of revenues and customs and administration of civil justice. The company assumed the power of civil and revenue administration while the administration of criminal justice still remained with the Nawab or the Nizam. The maintenance of army was, however, taken over by the Company.

The Company preferred to execute its Diwani functions through the natives under the supervision of its officials instead of appointing its own English servants for this purpose.The dual system of government introduced in 1765 by Clive, consequent to taking over of diwani by Company, did not prove a successful venture. The reasons were obvious. The Indian officials had no effective power to enforce their decisions nor could they dare to take action against the English servants of the Company. The Supervisors also did not have adequate training and experience to perform their duties efficiently. The natural calamities like famine during 1770-71 made the situation worse. The Company appointed Warren Hastings as Governor of Bengal to execute the changed policies regarding diwani functions.

Hastings’s Judicial Plan of 1772

The administration of justice at the time Warren Hastings took over as Governor of Bengal was in a bad shape. He appointed a committee consisting of the Governor and four members of the Council called the ‘Committee of Circuit’. The Committee prepared a Judicial Plan on August 15, 1772 to regulate the administration of Justice and revenue collection. This plan was popularly known as the ‘Hastings’ Plan of 1772. The Judicial plan of Warren Hastings consisted of 37 regulations dealing with civil and criminal laws. He divided the diwani area of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa into several districts, each having an English officer called the ‘Collector’ as its head. Thus ‘district’ was the unit of administration for justice and revenue collection. The Collector was primarily responsible for collection revenue. The main features of Judicial Plan of 1772 may be explained under the following headings:

- Revenue Administration: The whole revenue system was re-organised under the Hastings Plan of 1772. A supreme authority called the Board of Revenue was set up at Calcutta which consisted of the Governor and all the members of the Council. All orders were to be issued by the Collector under the Company’s seal and funds were to pass through him to the treasure at Calcutta. The Board of Revenue comprising Governor and his Councillors at Calcutta sat twice a week for issuing necessary orders and instructions to the Collectors of Districts and inspecting, auditing, and passing the revenue accounts.

- Administration of Civil Justice: In each district, a Mofussil Diwani Adalat was established which was presided over by the Collector as Judge. The Court took cognizance of all civil cases including property, inheritance, succession, castes, marriage, contracts, accounts etc. The cases relating to caste, religion, marriage and inheritance of the natives were to be decided according to their usages and customs of Hindu law for Hindus and Muslim law for mohammadans was applied. The Collector being an Englishman, was ignorant about the personal laws of natives, hence he was assisted by native laws officers called Kazi and Pandits who expounded the law to him. Appeals from these courts were to be heard by the Sadar Diwani Adalat at Calcutta where the subject matter of the case exceeded rupees 500. The Judicial Plan of 1772 had two distinctive features, namely, English law was not applied for the natives in the provinces, and Hindus and Muslims were treated equally without any discrimination.

- Improvement in Procedure for civil Justice: The Judicial Plan of 1772 laid sufficient stress on providing easy access to justice through the courts. The Collectors were directed to place a complaint box at the door of each Cutcherry wherein the complaints, could lodge their petition at any time.

- Provision of Arbitration by consent: Under the Warren Hastings’s judicial Plan of 1772, a provision regarding arbitration by consent, as opposed to compulsion in the old system, was made in matters of contract, partnership, debts, disputed accounts etc. In cases of inheritance, caste and religious usages, the law of Quran for Muslims and law of Shastras for Hindus were binding. The moulvis and pundits expounded law and helped the Collector in deciding civil cases in the mofussil diwani Adalats.

- Administration of Criminal Justice: The Judicial Plan 1772 provided for establishment of a Court of Criminal Judicature called the Fauzdari Adalat in each district which tried serious offences including murder, robbery, theft, fraud, perjury etc. This Court was assisted by a kazi or mufti and two moulvis who expounded the mohammedan law of crimes. The mufti function was to expound the law and give ‘fatwa’ after hearing the parties in evidence. But the Collector exercised overall supervision on the working of the Fouzdari Adalat. Besides Fouzdari Adalats in the districts, a superior court called the Sadar Nizamat Adalat was also established at Calcutta which exercised control over Fouzdari Adalats. It was presided by an Indian judge known as the Daroga-i-Adalat who was to be assisted by the Chief Kazi, chief Mufti and three Moulvis. These persons were appointed by the Nawab on the advice of the Governor. Thus, fouzdari adalats were not empowered to award death sentence, but they were required to transmit the evidence in capital cases with their opinion to the Sadar Nizamat Court for final decision. The dacoits were to be executed in their own village and the entire village was fined. The family members of the dacoits were made State-laves.

Judicial Plan of 1774

Warren Hastings prepared a new plan on November 23, 1773 which was implemented in January 1774. Under the Judicial Plan of 1774 the entire diwani area of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa was divided into six divisions with headquarters at Calcutta, Burdwa, Murshidabad, Dinajpore, Dacca and Patna. Each division consisted of several districts. A ‘Provincial Council’ consisting of five covenanted servants of the Company was established in each of these divisions except Calcutta where a ‘Committee of Revenue’ was set up. These Councils supervised the revenue collection in the Division and heard appeals from the mofussil diwani adalats from the districts within its territorial jurisdiction. The post of Collector having been abolished in 1773 now each district was places, in charge of an Indian officer called the ‘Diwan’ or the ‘Amil’. His main function was to look after the work of revenue collection in his district. He also presided over the Mofussil Diwani Adalat of the district which was previously presided by the Collector.

Judicial Plan of 1780

The outstanding feature of the judicial plan of 1780 was separation of judicial functions from those of revenue collection. A new court, called the provincial Court of Diwani Adalat was established at each of the headquarters of the six Divisions. This Adalat was presided over by an English covenanted servant of the Company who was called the Superintendent of the Diwani Adalat. He was to be appointed by the Governor-General and Council. The decision of the provincial Court of Diwani Adalat in cases up to the value of Rs.1,000/- was final and in cases exceeding this value, an appeal lay to the Sadar Diwani Adalat at Calcutta which consisted of the Governor General and Council. However, Sir Elijah Impey was appointed as the sole judge of the Sadar Diwani Adalat in October, 1780. He introduced major reforms in the judicial scheme introduced by the judicial Plan of 1780. He extended whole hearted support to Warren Hastings in establishing an effective judicial system in the territories of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa.

Judicial Reforms of Lord Cornwallis (1787-1793)

Lord Cornwallis succeeded Warren Hastings a Governor-General in 1786. Before assuming the office of the Governor General, he laid down two conditions, namely:

- That he would also be appointed as he Commander in Chief, and

- That Governor-General would be empowered to over-rule the decision of his Council whenever it was deemed necessary.

Lord Cornwallis period as Governor-General from 1786-1793 would be memorable in the legal history of India for introducing the principle of administration according to law and local usages of the country. He reorganised the entire revenue and judicial administration in three distinct phases through his judicial Plans of 1787, 1790 and 1793.

Judicial Plan of 1787

On the instructions from the Court of Directors, Lord Cornwallis introduced his first Judicial Plan in 1787 to combine revenue and judicial functions in a single authority called the ‘Collector’. The scheme was introduced through two Regulations, one dealing with revenue administration while the other with the administration of justice.

With a view to reorganising the revenue administration, the number of districts in Bengal, Bihar and Orissa was reduced from 36 to 23. An English covenanted servant of the Company was to be appointed as the ‘Collector’ who was in-charge of the district and was responsible for the collection of revenue within the district. He was to decide all revenue cases arising in the district in the revenue court called the Mal Adalat to be presided over by him. The salaries of collectors were raised to ensure purity and fairness in the administration of justice.Besides revenue collection, the collector was also to act as the Judge of the Mofussil Diwani Adalat for deciding civil cases. He was also to act as a magistrate of the District under his charge and apprehend and prosecute the offenders to be sent to Nizamat Adalat for trial. He could try petty offences himself, the punishment for which could not exceed 15 strokes or imprisonment for 15 days.Though the functions of revenue collection and administration of civil and criminal justice were re-united in a single person, namely, the Collector, yet he was to keep these various functions separate from each other as far as possible.

Appeals

Appeals from the decisions of the Mal Adalat which was headed by the Collector lay to the Board of Revenue at Calcutta and a further appeal from the Board of Revenue could be preferred to the Governor-General and Council. Thus there was provision for two appeals in revenue cases. In the Civil cases, an appeal from the Mofussil Diwani Adalat could be preferred to the Sadar Diwani Adalat if the subject matter of the suit exceeded Rs. 1000/- and in cases involving more than 5000 pounds a further appeal lay to the King-in-Council. The Sadar Diwani Adalat consisted of the Governor-General and all the members of his Council who were assisted by the Chief Kazi, Chief Mufti and two Moulvis who were to expound the Muslim law. The Hindu Pandits assisted the Court in expounding Hindu law.

Judicial Plan of 1790

Lord Cornwallis focused his attention on the reorganisation of the criminal justice through his Judicial Plan of 1790. The Judges of the criminal courts were poorly paid hence they tended to be dishonest and corrupt which resulted into inefficiency of the criminal justice system. There was a general deterioration in the law and order situation and unprecedented rise in crimes of dacoities, robberies, murders, etc. The law of evidence under the Mohammedan criminal law was also most unsatisfactory and irrational. For example, a Muslim murderer could not be convicted on the evidence of a non-Muslim and one Muslim witness was equivalent to two Hindu witnesses. Again, the evidence of two women was regarded as equivalent to one male witness. A person could not be convicted for the offence of rape unless four eye-witnesses actually testified the occurrence of the offence. Therefore, Lord Cornwallis introduced certain reforms in the then existing Mohammedan law of crimes and the organisation of the criminal courts. He formulated a new scheme of criminal justice system on December 3, 1790 under his judicial Plan of 1790. The main changes introduced under the Plan were as follows:

- Reforms introduced in Mohammedan Law of Crimes: Lord Cornwallis introduced certain modifications in the Muslim law of crimes which had far-reaching effect in improving the quality of criminal justice. In awarding sentence in case of murder, the intention of the accused rather than the manner or instrument employed for committing the offence was to be taken into consideration by the Judge. The right of the relative of the murdered person to pardon the murderer was withdrawn forthwith. The punishment of mutilation was abolished in 1791 and in its place imprisonment with hard labour for 14 years and 7 years was substituted for the loss of two limbs and one limb respectively. The capital sentence was to be passed only the Sadar Nizamat Adalat. The law of evidence was further modified in 1792 and discriminatory provisions relating to religion and sex were abolished and now the witnesses were to be treated alike, whether they are male or female; Hindu or Muslim. Now the evidence of a non-Muslim was also admissible in the trial of a Muslim for the offence of murder. Thus the existing criminal law was rationalised by Cornwallis by removing disparities which were based on religion and showed undue leniency towards Muslims in matters of crime.

- Reorganisation of the Criminal Courts: In order to improve the working of the criminal court, Cornwallis reorganised them in order to make justice speedy and accessible to a common man. The existing Mofussil Fouzdari Adalat were abolished and three distinct types of Courts were established, namely, the Court of District magistrate, the Court of Circuit and the Sadar Nizamat Adalat.

- The Court of District magistrate - The Collector of every district was to act as a District Magistrate. He was to apprehend offenders and try those petty cases himself which were punishable up to 15 strokes of imprisonment not exceeding 15 days. He was also empowered to conduct preliminary enquiry in case of murder, thefts, robberies and other offences and could acquit the offenders if charges against them were vague and baseless.

- Courts of Circuit - For the sake of administrative convenience, the entire territory of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa was divided into four Divisions, viz; Calcutta, Patna, Daccan and Murshidabad and a Court of Circuit were established in each of these Divisions. The court of Circuit was a mobile court. It consisted of two English Judges who were to be covenanted servant of the Company. They were to be assisted by the Muslim law officers, namely, kazis and muftis who were nominated by the Governor-General and Council. All Indian and Europeans other than the British subjects were placed under the jurisdiction of the Court of Circuit.

- The Sadar Nizamat Adalat - The Nawab was divested of all the powers of criminal adjudication and Mohammed Raza khan who controlled the Sadar Nizamat Adalat at Murshidabad was removed from his office. The seat of Sadar Nizamat Adalat was transferred from Murshidabad to Calcutta and it was now to consist of the Governor-General and the Members of his Council. They were assisted by Chief Kazi and two Muftis in their work. The Kazi and Muftis expounded the Muslim personal law. The Adalat was empowered to recommend the cases to the Governor-General and Council for mercy. The cases referred to the Dadar Nizamat Adalat by the Court of Circuit were to be reviewed by the Muslim law officers who were to apprise the Sadar Adalat whether the fatwa expounded by the native law officers of the Court of Circuit was in conformity with the law or not. The final decision, however, lay with the Sadar Nizamat Adalat.

Judicial Plan of 1793

In order to remove the shortcomings of the scheme of 1787, Lord Cornwallis brought about vital changes in the administration of civil justice through his Judicial Plan of 1793. A Code called the ‘Cornwallis Code’ consisting of 48 Regulations was introduced by him.

- Separation of Civil and Revenue jurisdiction - After 6 years experience with the combination of revenue and judicial functions in the Collector, Cornwallis realised that it was in the interest of administration of civil justice to revert back to separation between the judicial and revenue functions as it existed prior to his Plan of 1787. Under the Judicial Plan of 1793, the Collector was only to collect the revenue and his power to decide revenue and civil cases was withdrawn and transferred to the Mofussil Diwani Adalat. The Mal-Adalats were abolished from May 1, 1793 and the Collector was now to collect revenue under the supervision of the Board of Revenue which was controlled by the Governor-General and Council at Calcutta.

- Re-organisation of Diwani Adalats - The working of civil courts was reorganised by Regulation III of the Cornwallis Code so as to make them more independent and efficient. A Mofussil Diwani Adalat was established in each district of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa and a civil servant of the Company was appointed as Judge of the Adalat in place of Collector. The principle of judicial control over executive actions of the Government was introduced in India for the first time thorugh the Judicial Plan of 1793. The Diwani Adalat was not to interfere in criminal adjudication.

- Appeals from the Diwani Adalats - Appeals in all civil cases, irrespective of the value of the subject matter, could be preferred to the Provincial Court of Appeal which was created in each of the four Divisions of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa, namely, Patna, Calcutta, Dacca and Murshidabad. This Court consisted of three English judges of the Company and it was an appellate court for the division.

- Abolition of Court-Fees - Another significant change introduced by Lord Cornwallis through his Judicial Plan of 1793 was the abolition of Court-fees. The litigants were not required to pay any fees excepting the pleaders fees and actual charges incurred on summoning the witnesses

- Administration of Criminal Justice - The Magisterial power of the Collector was transferred to the judge of the Mofussil Diwani Adalat with the same powers and functions. The Judge-Magistrate could decide petty criminal cases which could be punished by imprisonment up to 15 days or fine up to Rs.100/-. Another change introduced was that the Court of Circuit created in 1790 and the Provincial Court of Appeal proposed in 1793 were merged to create four Courts of Appeal and Circuit, one each at Calcutta, Dacca, Patna and Murshidabad.

- Making of laws and Regulations - Cornwallis made an attempt to bring about uniformity in the pattern of Regulations. He provided that every Regulation shall contain a preamble stating the reasons and objectives for its enactment. All Regulations passed in a year were to be printed and bound up in volumes and adequate arrangements were made to supply them to all the courts. They were to be translated into Persian and Bengali languages for the convenience of the public in general. The system of Regulation law ensured uniformity and certainly in the administration of justice.

- Permanent settlement of Land Revenue - The Zamindars were made the owners of the land and required to pay 9/10thof the revenue collection to the Government. This was a positive step in the right direction which ended the uncertainty of Zamindar’s position in relation to their Zamindari lands and their earnings from revenue collection.

- Reforms in the Police System - The Judicial Plan of 1793 restructured the entire Police system of the territories of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Each district was divided into police jurisdictions of 20 miles each. Further, each area was guarded by a Darogah with an armed constabulary. The Darogahs were to be appointed by the Magistrate. The cities of Dacca, Patna and Murshidabad were divided into wards, each of which was guarded by a Darogah who was under direct control of the Kotwal. The Police officials, namely Darogah and Kotwals were to apprehend the criminals and prevent the incidence of crime. They were to also responsible for maintenance of peace and order within the area under their guard.

- Creation of subordinate Civil Courts: Besides the Mofussil Diwani Adalat in each district, a number of subordinate courts were created by Regulation IX of the Cornwallis Code with a view to ensuring administration of civil justice to natives of interior parts of the district. The entire judicial work was concentrated in the single court, namely, the Mofussil Diwani Adalat which was set up at the District headquarters. This created problems for the litigants and witnesses to cover long distances to reach the district headquarters. Therefore, Cornwallis introduced a subordinate judicial service for the interior parts of the district. The following courts constituted the subordinate judicial service-

- Munsif’s Court: In each district, Sadar Amins and Commissioner’s who were subsequently called the ‘munsifs’, were appointed to decide cases up to Rs.50/-. The appointment of Munsifs was made from amongst the landlords, farmers and Tehsildars etc. They were appointed by the Mofussil Diwani Adalat with the approval of the Sadar Diwani Adalat. They were honorary judge without any paid salary but received commission for their work. Indians could be appointed as Munsifs. An appeal from the decision of munsif lay to the Mofussil Diwani Adalat and a second appeal could be preferred to the Provincial Court of Appeal of the Division.

- Registrar’s Courts: There was yet another subordinate court called the Registrar’s Court which functioned under the Mofussil Diwani Adalat of the district. The Mofussil Diwani Court could authorise the Registrar’s Court to decide cases up to rs.200/-. However, the decision of the Registrar had to be countersigned by the judge of the Mofussil Diwani Adalat. The decisions of the Registrar’s Court were subject to revision by the judge of the Mofussil Diwani Adalat. Only a covenanted English servant of the Company could be appointed as a Registrar.

Infamous trial of Raja Nand Kumar

He was India's first victim of hanging under British rule. He was appointed by the East India Company to be the collector of taxes for Burdwan, Nadia and Hoogly in 1764. Raja Nand Kumar, a Hindu Brahmin was a big Zamindar and a very influential person of Bengal. He was loyal to the English company ever since the days of Clive and was popularly known as “black colonel” by the company. Three out of four members of the council were opponents of Hastings, the Governor-General and thus the council consisted of two distinct rival groups, the majority group being opposed to Hastings. The majority group comprising Francis, Clavering and Monson instigated Nand Kumar to bring certain charges of bribery and corruption against warren Hastings before the council whereupon Nand Kumar in march, 1775 gave a latter to Francis, one of the members of the council complaining that in 1772, Hastings accepted from him bribery of more than one Lakh for appointing his son Gurudas, as Diwan. The letter also contained an allegation against Hastings that he accepted rupees two and a half lakh from Munni begum as bribe for appointing her as the guardian of the minor Nawab Mubarak-ud-Daulah. Francis placed his letter before the council in his meeting and other supporter, monsoon moved a motion that Nand Kumar should be summoned to appear before the Council. Warren Hastings who was presiding the meeting in the capacity of Governor-General, opposed Monson’s motion on the ground that he shall not sit in the meeting to hear accusation s against himself nor shall he acknowledge the members of his council to be his judges. Mr. Barwell ,the alone supporter member of Hastings ,put forth a suggestion that Nand Kumar should file his complaint in the supreme court because it was the court and not the council ,which was competent to hear the case. But Monson’s motion was supported by the majority hence Hastings dissolved the meeting. Thereupon, majority of the members objected to this action of Hastings and elected Clavering to preside over the meeting in place of Hastings .Nand Kumar was called before the council to prove his charges against Hastings. The majority members of the council examined Nand Kumar briefly and declared that the charges levelled against Hastings were proved and directed Hastings to deposit an amount of Rs.3, 54,105 in treasury of the company, which he had accepted as a bribe from Nand Kumar and Munni Begum. Hastings genuinely believed that the council had no authority to inquire into Nand Kumar’s charges against him. This event made Hastings a bitter enemy of Nand Kumar and he looked for an opportunity to show him down.

Soon after, Nand Kumar was along with Fawkes and Radha Charan were charged and arrested for conspiracy at the instance of Hastings and barwell. In order to bring further disgrace to Raja Nand Kumar, Hastings manipulated another case of forgery against him at the instance of one Mohan Prasad in the conspiracy case. The Supreme Court in its decision of July 1775 fined Fawkes but reserved its judgment against Nand Kumar on the grounds of pending fraud case. The charge against Nand Kumar in the forgery case was that he had forged a bond in 1770. The council protested against Nand Kumar’s charge in the Supreme Court but the Supreme Court proceeded with the case unheeded. Finally, Nand Kumar was tried by the jury of twelve Englishmen who returned a verdict of ‘guilty’ and consequently, the supreme court sentenced him to death under an act of the British parliament called the Forgery Act which was passed as early as 1728. Serious efforts were made to save the life of Nand Kumar and an application for granting leave to appeal to the king-in-council was moved in the Supreme Court but the same was rejected. Another petition for recommending the case for mercy to the British council was also turned down by the Supreme Court. The sentence passed by the Supreme Court was duly executed by hanging Nand Kumar to death on August 5, 1775. In this way, Hastings succeeded in getting rid of Nand Kumar.

Judicial Reforms of Lord William Bentinck

Lord William Bentinck succeeded Lord Amherst and took over as Governor General in July 1828 and continued up to March 1835. Lord William Bentinck reorganised the entire judicial administration by introducing the following changes in the criminal as well as civil judicature:

Reforms in Criminal judicature (1828-29)

- The first step taken by Lord Bentinck was abolition of the Provincial Courts of Appeal and Circuit in 1829 as they failed to render the trials cheap and speedy. The reason for this was that the judges of these Courts were entrusted with multifarious functions of supervising the executive and revenue officers, performing magisterial functions as also the duties of police. For the same reason the Judges of the Circuit could hardly find time to acquaint themselves with the local languages and customs. In order to improve this situation, Lord Bentinck divided the entire territory of Bengal into 20 divisions each having a Commissioner of Revenue and Circuit. They were to exercise supervisory powers over the Collector of revenue and supervise the functions of the police in their division. These Commissioners were under the control of Sadar Nizamat Adalat for their judicial functions and under the Sadar Board of Revenue for their revenue duties. Their orders were final and conclusive not being subject to revision by the Sadar Nizamat Adalat.

- The appeals from the decisions of magistrates wee to be taken to the Commissioners of Revenue and Circuit. This provided great relief to the litigants.

- The sentencing power of the magistrate was extended to two years imprisonment with hard labour by Regulation VI of 1829.

- The practice of Sati prevalent among Hindus, especially the Rajputs, was declared an offence and the abetment of this offence was also made punishable.

- In 1830, a provision was made which empowered the government to appoint a native gentleman as a law officer and the trial held with the assistance of such law officers was to be valid.

Reforms of 1831 in Criminal Judicature

- A District and Sessions Court was established in each district which was empowered to hear and decide civil and criminal cases. Regulation VII of 1831 authorised the Governor-General in council to empower the judges of the District Diwani Adalat not being magistrate, to hold criminal sessions whenever the pressure of work on the Commissioner was too heavy. In course of time, a District and Sessions Court was set up in each district to relieve the Commissioners of their heavy work load. This Court was to decide both, civil and criminal cases. The system continues even to this day.

- In 1831, a Sadar Nizamat Adalat was established at Allahabad to supervise the administration of justice in North-West Provinces. It had the same powers as that of the Sadar Nizamat Adalat of Calcutta.

- Unlike Lord Cornwallis, William Bentinck favoured the inclusion of native Indians to judicial posts. In 1832, the Sadar Ameens, who were Indian law officers, could award punishment of imprisonment with hard labour and corporal punishments upon the persons accused of theft. The Commissioners of Circuits could, take assistance from the native law officers by employing them as jurors of assessors. One important change introduced by Lord Bentinck was that non-Muslims could seek exemption from being tried in accordance with the Mohammedan law of crimes. Thus it would be seen that Muslim law of crime ceased to be applicable to all the natives alike.

Reform in Civil Justice

Lord William Bentinck modified the system of civil administration of justice through the scheme of 1831 as mentioned below:

- The munsifs could now decide all suits up to the value of Rs.300/- the natives were eligible for appointment as munsif without any restriction of caste, creed or religion. They were to be the regular salaried officers of the Government.

- The Office of Sadar Ameen was also thrown open to natives. Suits not exceeding the value of Rs.1000/- could be referred to a Sadar Ameen by the Zilla or City Judge. One more higher cadre of Ameens, called the Principal Sadar Ameen was created. They were also salaried officers of the Government. The Zilla or City Diwani Judge could refer to a Principal Sadar Ameen, any case not exceeding Rs.5000/-. in value.

- The Provincial Courts of appeal were abolished in 1833. As regards the appeals, the decision of the Zilla or City Diwani Adalat was final in suits which came in appeal from the Court of munsifs or Sadar Ameen.

- All British subjects, European and American foreigners were excluded from the jurisdiction of native judges of all categories.

- The Registrar’s Courts were abolished consequently, the earlier procedure of referring civil suits to the Registrar of the Zila or City Diwani Adalat was abolished and such cases were now to be sent to Sadar Ameens or the Principal Sadar Ameen for reference according the pecuniary value of the suit.

- Regulation V of 1832 provided that the English officials of the civil courts could seek assistance of respectable native gentleman in deciding civil cases either by referring the suit to a ‘Panchayat’ to find the facts and report to the court or deputing two or more of such natives as ‘Assessors or by employing them as ‘Jury” to attend the Court during trial and give their verdict. Thus, this marks the beginning of Jury system in India. However the final decision was always vested with the Judge of the court in all cases.

- Like a Sadar Nizamat Adalat, a Sadar Diwani Adalat was also established at Allahabad from January 1, 1832, for the North-West Provinces with the same powers as that of the Sadar Diwani Adalat of Calcutta.

Reforms in Revenue Administration

The combining of judicial and revenue functions in a single authority by the Judicial Reforms of 1829 adversely affected the efficiency of the Judicial administration and revenue earnings of the Company. Consequently, the system was discarded through Regulation VII of 1831.

The Charter Act of 1833

The Charter Act of 1833 was passed in the British Parliament which renewed the East India Company’s charter for another 20 years. This was also called the Government of India Act 1833 or the Saint Helena Act 1833.

Features of the Charter Act of 1833

- The company’s commercial activities were closed down. It was made into an administrative body for British Indian possessions.

- The company’s trade links with China were also closed down.

- This act permitted the English to settle freely in India.

- This act legalised the British colonisation of the country.

- The company still possessed the Indian territories but it was held ‘in trust for his majesty’.

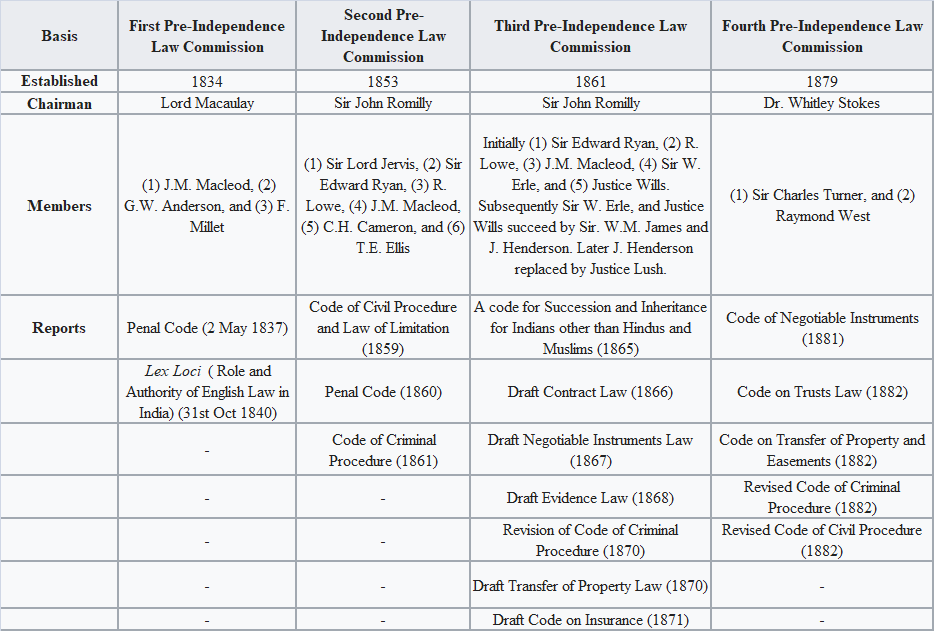

Indian Law Commission

- The act mandated that any law made in India was to be put before the British Parliament and was to be called ‘Act’.

- As per the act, an Indian Law Commission was established.

- The first Law Commission had Lord Macaulay as its chairman.

- It sought to codify all Indian law.

Significance of the Charter Act of 1833:

- It was the first step in the centralisation of India’s administration.

- The ending of the East India Company’s commercial activities and making it into the British Crown’s trustee in administering India.

- Codification of laws under Macaulay.

- Provision for Indians in government service.

- Separation of the executive and the legislative functions of the council.

LAW COMMISSIONS

Other Acts which were coded-

- 1870 - Court Fees Act

- 1870 - Land Acquisition Act

- 1870 - Female Infanticide Act

- 1870 - Female Infanticide Prevention Act

- 1870 - Hindu Wills Act

- 1872 - Code of Criminal Procedure (revised)

- 1872 - Indian Contract Act

- 1872 - Indian Evidence Act

- 1872 - Special Marriages Act

- 1872 - Punjab Laws Act

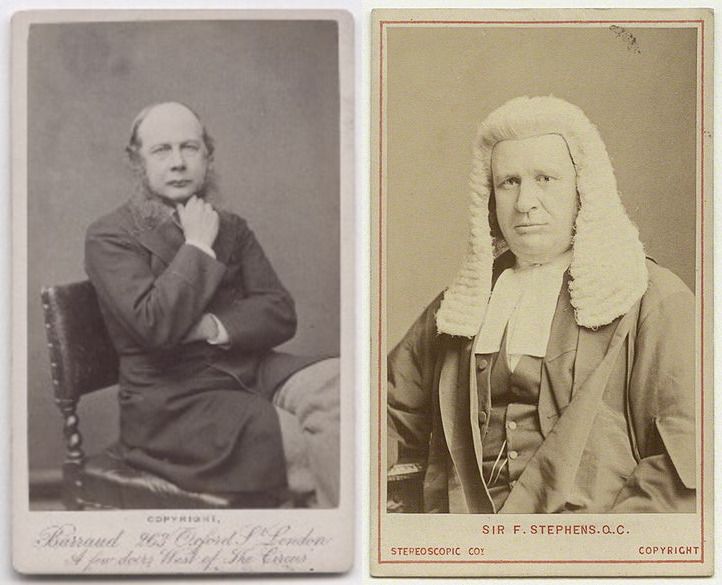

A Two-member Viceroy's Executive Council (composed of Sir Henry Maine and Sir James Fitzjames Stephen) also worked on the side-lines of the Law Commissions and ensured the passage of the following noteworthy laws:

- 1863 - Religious Endowments Act

- 1864 - Official Trustees Act

- 1865 - Carriers Act

- 1865 - Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act

- 1865 - Parsi Intestate Succession Act

- 1866 - Indian Companies Act

- 1866 - Native Converts Marriage Dissolution Act

- 1866 - Trustees Act

- 1866 - Trustees and Mortgage Powers Act

- 1867 - Press and Registration of Books Act

- 1868 - General Clauses Act

- 1869 - Divorce Act

Conclusion

With this part, comes to an end to one of the longest article I have ever written so far. We see the advent of the Englishmen to be one of the darkest episodes of the history of the land but we cannot deny the fact that they played a vital role in the social and legal transformation in India through their immense contribution in the form of various standardised acts which are still relevant in the prevailing times. And with the end of the British Rule in India came the birth of a democratic nation called the Free Independednt India and one of the lengthiest Constitution!

I would add a different post for the references of all the sources and books that has helped me to complete this series. I hope this article was informative and with this I end the series of 'The Indian Legal History- from the times of Origin of State to the English East India Company'.

Comments ()