The Indian Legal History- from the times of Origin of State to the English East India Company - PART-1 (Ancient India)

"In some respects the judicial system of ancient India was theoretically in advance of our own today."- John W. Spellman

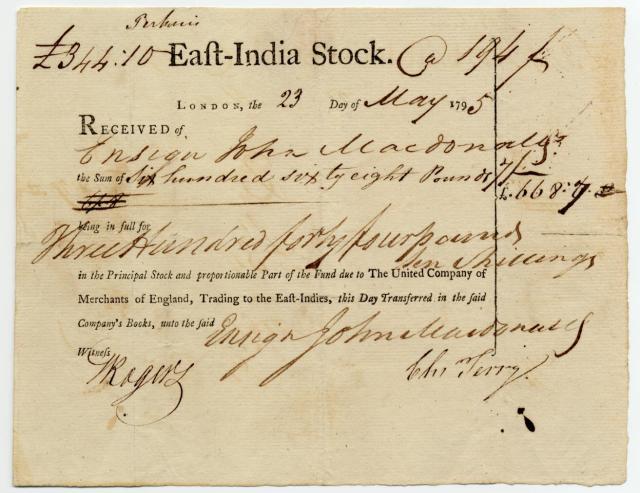

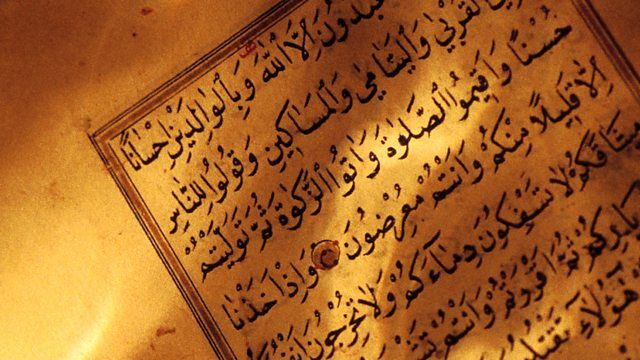

The Indian Judicial or Legal history has been the oldest in the world. No other legal or judicial system has a more ancient ancestry. From the times of the Mahabharata to the times of the English East India Company, the land of India has witnessed a vast experience of different judicial procedures, law and order that ruled the respective societies. With every new power emerging and with the birth of every new ruling dynasties came new law and order administering the peace and order of its people. The concept of Dharma that ruled the Indian civilization, from Vedic period to Muslim invasion was considered to be the ultimate rule that everyone followed. The word Dharma is derived from "dhr" to mean to uphold, sustain or nourish. With every new ruler that emerged, the civilization kept Dharma above all until it started to lose its strong relevance with the advent of the Britishers.

In order to understand the complex legal system of India, one has to go back to the times of the Ancient Indian state, the body that governed the state, the law and order which prevailed at those times to maintain public morality and peace. One should also go back to the times when India was ruled under two big Non-Hindu dynasties i.e., the Sultanates and the Mughals. The judicial body that prevailed in those periods took into consideration of the religious matters more often as there was emergence of conflict between the Hindus and that of Muslims which was sparked with the coming of the Britishers especially after the revolt of 1857.

Origin of the State in Ancient India:

We have only the uncertain light of legends and mythology to visualize the circumstances under which men for the first time associated themselves into a political organisation and established a ministry which also included the Law making body. We have occasional speculations on the origin of the State in the ‘Mahabharata’. The Shantiparva goes on to narrate that society flourished without a king or law court for a long time, but later somehow there was a moral degeneration. The law of the jungle began to prevail; the strong devour the weak, as is the order of the day among the fish (Matsyanyaya).

Hindu thinkers held that State was an indispensable institution for the orderly existence and progress of society in the imperfect world as known to us in historic times; a country without government cannot even exist. The idea of a primeval Golden Age is accepted only in some sections of the Mahabharata and Buddhist literature. Social Contract is possible only in a society where mutual rights and obligations are respected, and this is obviously impossible in a society where the law of the jungle prevails.The desire to put an end to anarchy and evolve a better type of society with law, order and government are stated to be the chief grounds for people entering into the original contract that brought government into existence with law and order governing various matters of the state.

Judicical System and Administration of Justice in Ancient India

We do not find references to any judicial organisation in the Vedic literature, which is at least a 1000 years earlier than the age of Manu. This is so because for a long time even murders were not regarded as offences against the state but as simple torts (civil wrong), where mere compensation had to be given to the relations of the party murdered. Vedic literature nowhere refers to the king as a judge either in civil or criminal cases. Offences like murder, theft and adultery are mentioned, but there is nothing to indicate that they were tried by the king or an officer authorised by him.Normally it was the sabha or the popular village assembly rather than the king who tried to arbitrate when it was feasible to do so. The terms Prasnin and Abhiprasnin referred the plaintiff and the defendant respectively who submitted their disputes for settlement before the village sabha. Madhamasi was rather an arbitrator than a judge who tried to settle the disputes rather than involving in giving punishments. Manu mentions the following grounds on which litigation was to be instituted-

- Breach of Contract

- Non-payments of debts

- Sale without ownership

- Deposits

- Partnership

- Non-payment of wages

- Disputes between owners and herdsmen

- Law on Boundary disputes

- Law concerning husband and wife

- Partition of Inheritance

- Gambling and betting

The Dharmasutras and the Arthashastra reveal to us a more or less full-fledged and well developed judiciary. The king was at its head and he was to attend the court daily to decide disputes. It was his sacred duty to punish the wrong-doer; if he flinched from discharging it, he would go to hell.

The Dharmasastra and Nitishastra literature regards the king as the fountain source of all justice. His time table required him to spend every day about a couple of hours in adjudication. In theory the king could entertain any suit, but in actual practice he could have looked into only the important cases from the capital. He was often too busy to do even this and used to delegate the work to the chief justice or to some other royal officer. The king decision was also the highest appellate decision. Narada points out how an appeal was possible to the city court against the village court decision, and how a litigant could appeal to the king against the decree of the city court. But whether a king decides a case properly or otherwise, there was no appeal against his decision. The king however was expected to be strictly impartial in deciding the cases or appeals that came before him. He was to decide according to law; otherwise he would be guilty.

JUDICIAL BODY

- Pradvivaka or the Chief Justice, who deputised for the king during his absence, was naturally a legal personality of high reputation. He was to be well versed both in substantive law as well as in the law of procedure. He was to be a master in the sacred as well as in the customary law.

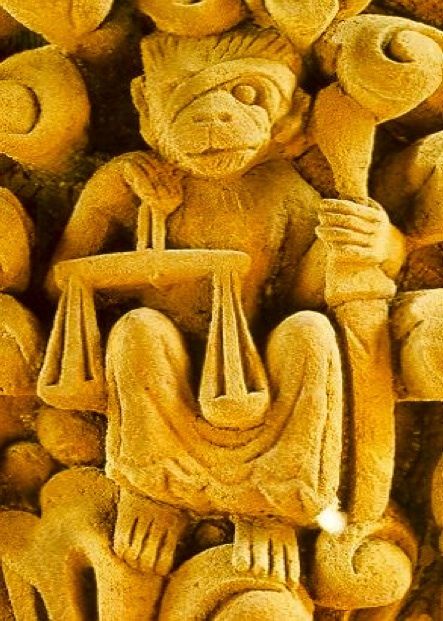

- The most interesting feature of the judicial administration was the system of jury (panel of judges). Even the king and the chief justice could not begin the trial of case, if they were not assisted by a panel of three, five or seven jurors. The number of jurors (Sabhyas) was deliberately kept uneven to provide for the contingency of a difference of opinion.They were to be fearless exponents of what they believed to be the correct legal position. A juror keeping prudent silence has been condemned. If necessary, the jurors were to express their opinion, even if it was in opposition to that of the king; it was their duty to restrain a wilful king going astray and giving a wrong decisions.The only exception was that of a difficult case, where the jurors could not come to any definite decision. In such case the king exercised his privilege of deciding the point according to his own view.The Smritis are almost unanimous in stating that the sabhyas or jurors should be Brahmanas. The study of the Dharmasastra was usually cultivated in the Brahmanical circles, and a deep knowledge of the sacred law was necessary for the proper discharge of the duties and functions of the juror.

COURTS

- When kingdom began to be fairly extensive ones after 600 B.C., subordinate royal courts began to be constituted for important towns and cities. To judge from the evidence of the Arthashastra, they were often located in the headquarters of territorial divisions, like Sthana (which included about 800 villages), Dronamukha (which comprised 400 villages) and Kharvatika,(which was exactly half the size of Dronamukha (200)). These courts functioned under the authority of the royal seal and were therefore called mudrita in later times.

- There were special royal courts of criminal jurisdiction, known as Kantakashodhana courts. According to the Arthashastra these courts took cognisance not only of the serious crimes against the state but also of offences against society. Thus if traders used false weights or sold adulterated goods, or charged excessive prices, if the labour in the factory was given less than a fair wage or did not do its work properly, the Kantakasodhana courts intervened to punish the culprits. Officers charged with misconduct, persons accused of theft, dacoit and sex-offences had to appear before the same court.

- Yajnavalkya mentions three types of popular courts, Puga, Sreni and Kula which were agencies of adjudication other than the official ones. Usually an appeal was made to Sreni Court from the decision of Kula court and the same may be appealed to Puga court from the decision of the Sreni court.

- Kulas or joint families were often very extensive in ancient India; if there was a quarrel between two members, the elders used to attempt to settle it. The Kula court was this informal body of family elders. When the effort at family arbitration failed, the matter was taken to the Sreni court. The term Sreni was used to denote the courts of guilds, which became a prominent feature of the commercial life in ancient India from 500 B.C. They are frequently mentioned in the Buddhist literature and the Mahabharata gives a glorious description of the guild chiefs’ assembled at the coronation of king Dharma (Yudhishtira). Srenis had their own executive committees of four or five members and it is likely that they might have functioned as the Sreni courts also for settling the disputes among their members. The Puga court consisted of members belonging to different castes and professions, but staying in the same village or town.

TYPES OF COURTS

Kautilya or Chanakya mentions two courts - Dharmasthiya (civil courts) and Kantakashodhana (criminal courts). The civil courts settled disputes which settled disputes relating to contracts, trespass, inheritance, marriages, labour etc. These courts were composed of six judges and were larger than the criminal courts.

According to Kautilya, the Criminal Law scourts took cognizance of the matters which involved the protection of the merchants &artisans, detecting criminals with the help of the spies, capital punishment, ravishment of immature girls and other miscellaneous offences.

Kautilya devotes a whole chapter in detail about the dismal and woeful aspects of law. The youngs, the aged, the diseased, the intoxicated, the insane, those who confessed guilt, the physcially weak, the pregnant women, and those who had not passed a month after delivery, were generally exempted from the torture of lawful punishments.

COURTS OF THE GUILDS

Guilds represented the working class who carried out important town activities which includes traders, industriesm artisans, craftsmen and blacksmiths. There was even the guild of theives. The guilds had their own rules and regulations called the Srenidharmas, which were binding on their members. The Dharmasastras recognised the validity of the laws and customs established by the guilds. Manu also recommends that Srenidharmas were also to be considered as a source of customary law.

THE ROLE OF THE JUDGES

The Ancient legal texts set a very high standard for its judges to maintain the public well being and peace and order.

- They were to be learned in various subject matters like moral science, philosphy, history, scientific theories and other important matters.

- They were to be through with the various religious aspect concerning to the matter that come up before him for settlement. And, he also has to follow the concept of Dharma while administering Justice.

- The Judge has to be devoid of anger and has to be reasonable or prudent enough to understand various different circumstances and try to solve them without any partiality.

- According to Arthashastra, Judges shall settle disputes free from all kinds of circumvention, with mind unchanged in all moods or circumstances, pleasing and affable to all.

- A judge cannot impose an unjust corporal punishment and if he does, he was either condemned to the same punishment or made to pay twice the amount of ransom leviable for that kind of justice.

- An ideal judge was to possess independence of character, great learning and better understanding of various branches of law and impartiality and should pronounce judgement only after due deliberation and enquiry.

- He was to be the guardian of the weak, a terror to the wicked and his mind was to be intent on nothing but equality and truth and he was to keep away from the the anger of the King.

LEGAL LITERATURE

Ancient Indian society was not static, but dynamic and the changing needs of the society had to be recognised first, followed by modification of the regulations to suit the changing needs of the society and then enforced. After the Vedic age, probably the sacrificial instructions of the Brahmanas became unclear necessitating the composition of a new group of texts to elucidate them. This special class of literature is designated as the Sutras. The term sutra originally meant a “thread”. A sutra is ‘a short rule, in a particular topic, forming a part of a particular book. Both by their form and object, the Sutras form a class by themselves’. During those days, instructions were given orally and this enabled summarising the entire exposition thereby rendering its easy memorising.

The Kalpa Sutras are the oldest sutra works. It divides itself into three classes, the Srauta Sutras, the Grihya Sutras and the Dharma Sutras. The Srauta Sutras are so called because they are based on Sruti (heard), the Vedas. They deal with Vedic sacrifices and are important “for the understanding of the cult of the sacrifice” as well as “for the study of the history of religion”.The Grihya Sutras deal with domestic religious ceremonies of samskaras. Estimating the relative importance of the Grihya and Srauta ceremonies.The Srauta and Grihya Sutras lay greater emphasis on the idea of social welfare and prescribe elaborate rules for the governing of the society concerning religion, domestic duties and mutual relations between different members of the society. The third class of textbooks are the Dharmasutras, the manuals of human conduct. They deal at length with the duties of varnas and ashramas, the social usages, customs and practises of every-day life. The beginnings of civil and Criminal Laws have to be assigned to this period.

The Dharmasutras are our earliest sources for Hindu Law, the most important being those attributed to Gautama, Baudhayana, Vasistha and Apastamba. The Gautama Dharmasutra which is the oldest is assigned to the sixth century and the remaining three are placed between the sixth and fourth centuries B.C.Later, from the early centuries of the Christian era onwards, the prose Dharmasutra texts were reworked in verse form and came to be called Dharmasastras or instructions in the Sacred Law. With the passage of time, it came to be realised that the Vedic hymns are not only difficult to comprehend but also to relate to current practise. They were found to be inadequate for the regulation of large segments of social life that had become complex.Ultimately, in cases of conflict the smriti came to represent an authority superior to that of the tradition, though the Vedas were not discarded altogether.The Dharmasastras combine the practical with the ethical. They deal with many topics like varnas, ashramas, their privileges, obligations and responsibilities; dharma of Kshatriyas and kings, judicial procedure, and the sphere of substantive law such as crimes and punishments, contracts, partition and inheritance, adoption, gambling, etc.The authors of the smriti literature were Brahmanas and naturally they represent their point of view. The Arthashastra was more secular in character and differs from smritis in many particulars. The Dharmasastra, true to its nature, lays the greatest emphasis on dharma, while the Arthashastra on artha. The Arthashastra do place a high value on dharma, but their chief concern was the treatment of central and local governments, taxation, the employment of sama and other upayas, with alliances and wars, appointment of officers, punishment and so forth.

CONCLUSION

The Judicial complexity and advancement in Ancient India is noteworthy and its rich legal works are still considered as pioneers. Kautilya's Arthashastra is one of the tremendous example. The legacy of such such a rich legal system was made more vast with the coming of the Medieval Period where India witnessed the ruling of Non-Hindu Dyansties on its land. The next part of this blog will discuss about the judicial system and administration of Justice under the Sultanate and the Mughal Period and will also expand its discussion to the Judicial administration of other Hindu Ruling Kings in Medieval India like that of Vijayanagara Empire's King Krishnadevaraya, and the Marathas. We would also the punishments that prevailed in those times and other judicial proceedings.

Comments ()